Some of the villages in the area have been taking the time to reflect on their history as they celebrate their 150th anniversaries from when they were established.

150 years.

A century and a half.

That only really boils down to roughly six generations or so ago, when weary families were stepping off boats, children clinging to mothers’ skirts, oxen pulling wagons heavy with the barest necessities.

And stretched before them? A vast and empty prairie — flat, treeless, full of uncertainty.

What brought those Mennonites here? What possessed them to cross the open sea and call Manitoba their home?

Conrad Stoesz, Archivist with the Mennonite Heritage Archives in Winnipeg, helps unpack those questions and offers his professional insight into the hopes, fears, and global events that set many of the region’s ancestors on their journey to the prairies.

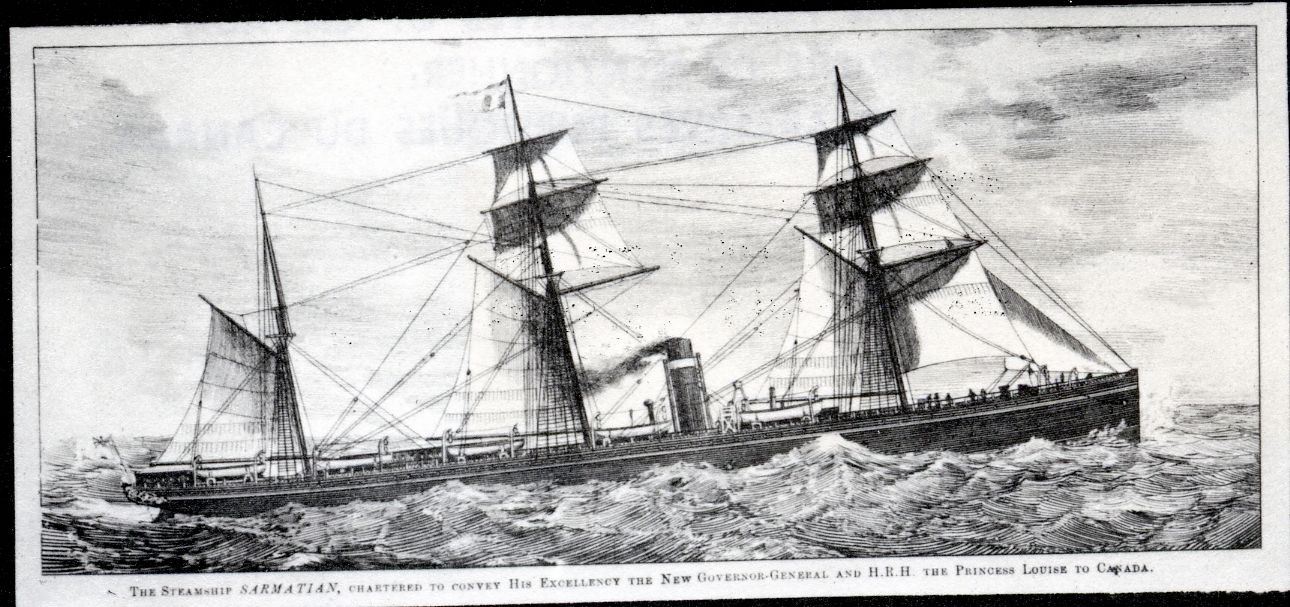

Sarmation — a ship that brought Mennonites to Canada - provided by Mennonite Heritage Archives

Sarmation — a ship that brought Mennonites to Canada - provided by Mennonite Heritage ArchivesThe Push...

It’s the 1850s, and Russia’s recent loss in the Crimean War has exposed the country’s weaknesses to itself, prompting a series of major reforms.

“One of those things was the loss of exemption from military service, and that they wanted more control over education,” Stoesz shared.

While some of the Mennonites living in what is now the current day Ukraine felt that they could work with the changes being made, that was not the case for everyone.

“Other Mennonites said, ‘No, I think we need to find another place to go. This is not acceptable,” he continued, adding that in 1873, delegates were sent from Ukraine and Imperial Russia to North America to find potential places to move to.

And North America just so happened to be looking for farmers.

“In the middle of summer [1875], there’s this infestation of Rocky Mountain Locusts... these things ate everything. All the crops, all the gardens, even some of the clothes hanging on the line.”

The Pull...

As the delegates made their way through these areas, they received a letter of invitation from the Canadian government.

Stoesz called it, “A fifteen-point document saying, ‘If you move to this new province of Manitoba, these are things we will provide.’”

On that list, amongst the land and building materials, were the key things that the Mennonites were looking for in their next home: exemption from military service, freedom of religion, and the ability to run their own schools.

“The Americans they offered land and some help in coming to North America. But they did not offer exemption from military service or the ability to run their own schools. And so, some Mennonites chose to go to the United States, about 10,000,” he said, “And 7,000 chose to go to Manitoba.”

“They’re [Mennonites] facing down starvation. So, they get help from the Mennonites from Ontario and the Federal Government... $100,000 from the Canadian Government, known as the ‘Bread Debt’, or ‘Brot Schuld’... And they pay it all off in 1892.”

Related stories:

- Win $1,000 by exploring Central Manitoba this summer

- Pauls looking forward to representing Manitoba at upcoming Western Canada Track Challenge

East and West Reserve

The first Mennonites to arrive in Manitoba were given land in what is now known as the Steinbach, RM of Hanover area, but at the time was known as the East Reserve.

“The first group came in 1874; they landed on the junction of the Red and Rat River. On the evening of August 1st and August 2nd, they got off the boat and moved to some immigration sheds that were temporarily set up.”

The next group would be provided more land west of the Red River in the now Altona and Winkler areas, known at the time as the West Reserve.

“And the first group that comes in 1875 docks at Fort Dufferin, and there they have to wait six weeks.”

Six weeks crammed inside of barracks that were far too small for the number of people they were trying to house, to the degree that a young man by the name of Jacob Fehr calls it, “This place of mourning” in his diary.

Stoesz confirmed the reason being, “Because almost every day, there was a funeral for a child who had died.”

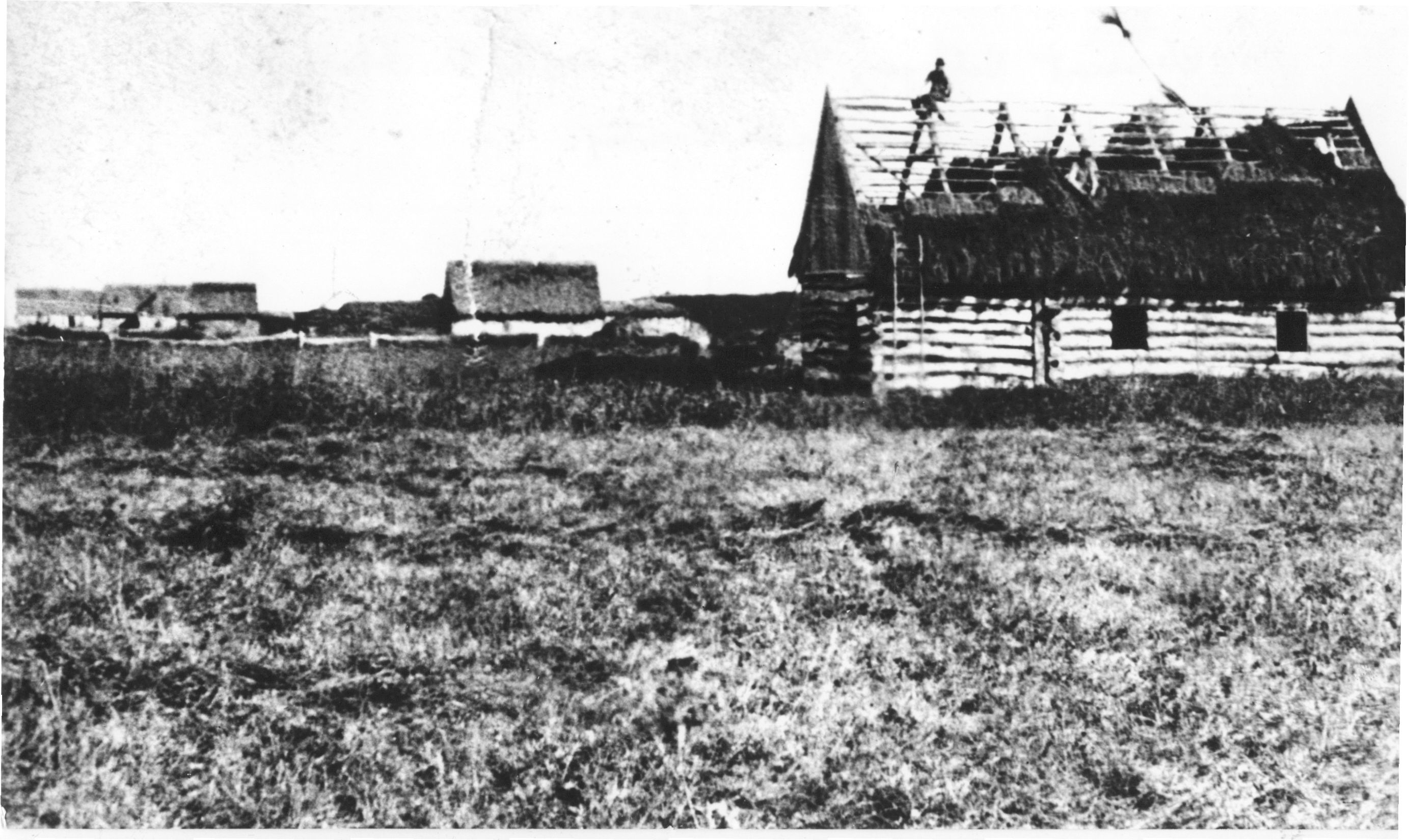

Putting on thatched roof on school in Blumenort Manitoba 1870s - provided by Mennonite Heritage Archives

Putting on thatched roof on school in Blumenort Manitoba 1870s - provided by Mennonite Heritage Archives“Now you have the Russian Revolution, and Mennonites in now Soviet Union wanted to get out... The CPR [Canadian Pacific Railway] said, ‘Yeah we can do that, but who’s going to pay for it?’... They were at an impasse.”

A new home

In August of 1875, the Mennonites left Fort Dufferin and began to establish their villages, which, according to Stoesz, was not what the government of Canada had anticipated.

“The Canadian government expected these new farmers to live on their own piece of land, their own quarter section. But the Mennonites wanted to live in villages, and that was very important.”

Having arrived in August, with not a lot of options on what can be planted and ready to eat before frost, living together in a community was not just a cultural preference, but necessary for survival.

“These villages allowed them to support each other physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually. So... the government allowed them what’s called the ‘Hamlet Privilege.”

This allowed the Mennonites to build these settlements accordance to their own needs, with their own language, and maintain their own culture. One built on community.

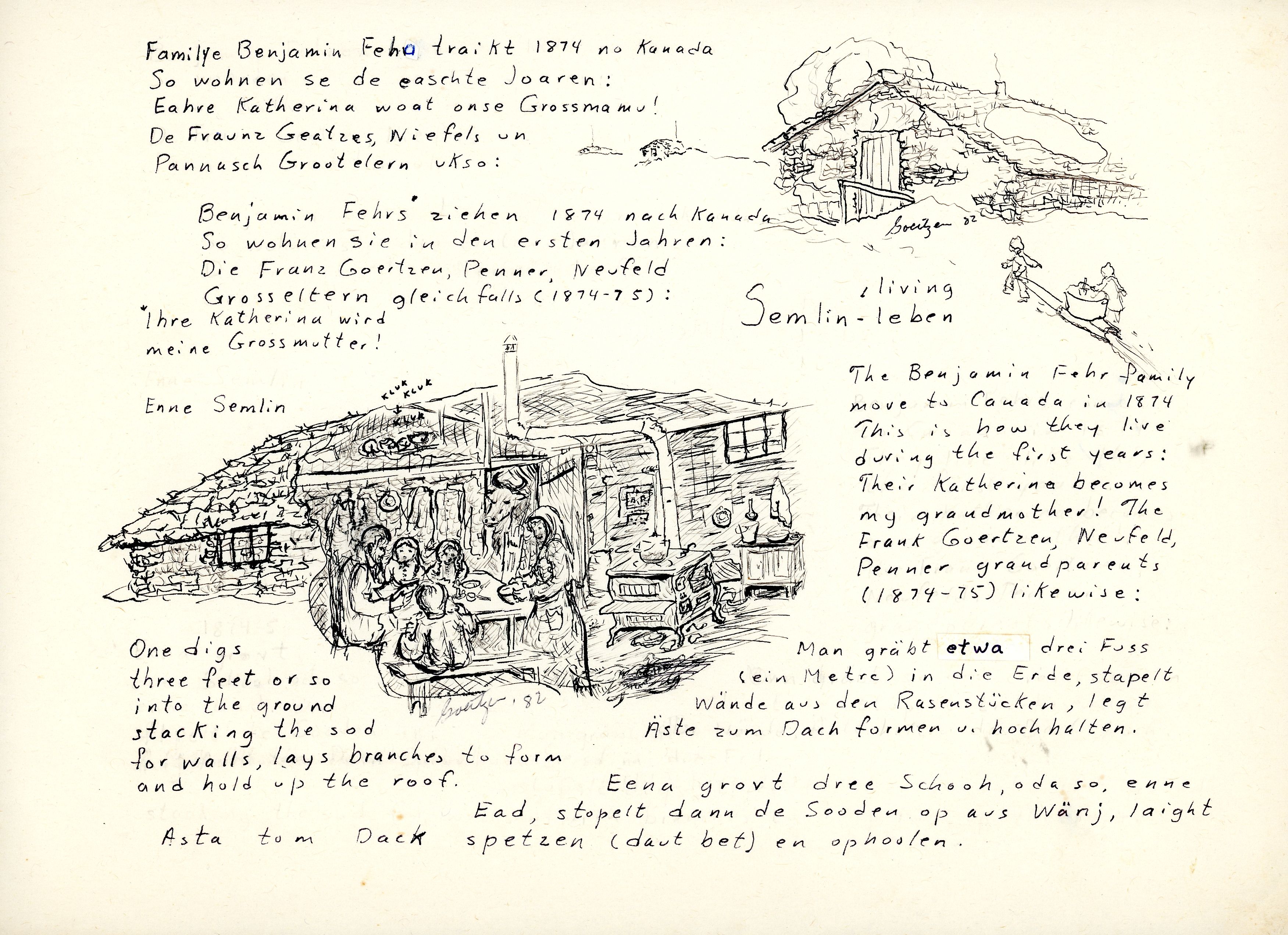

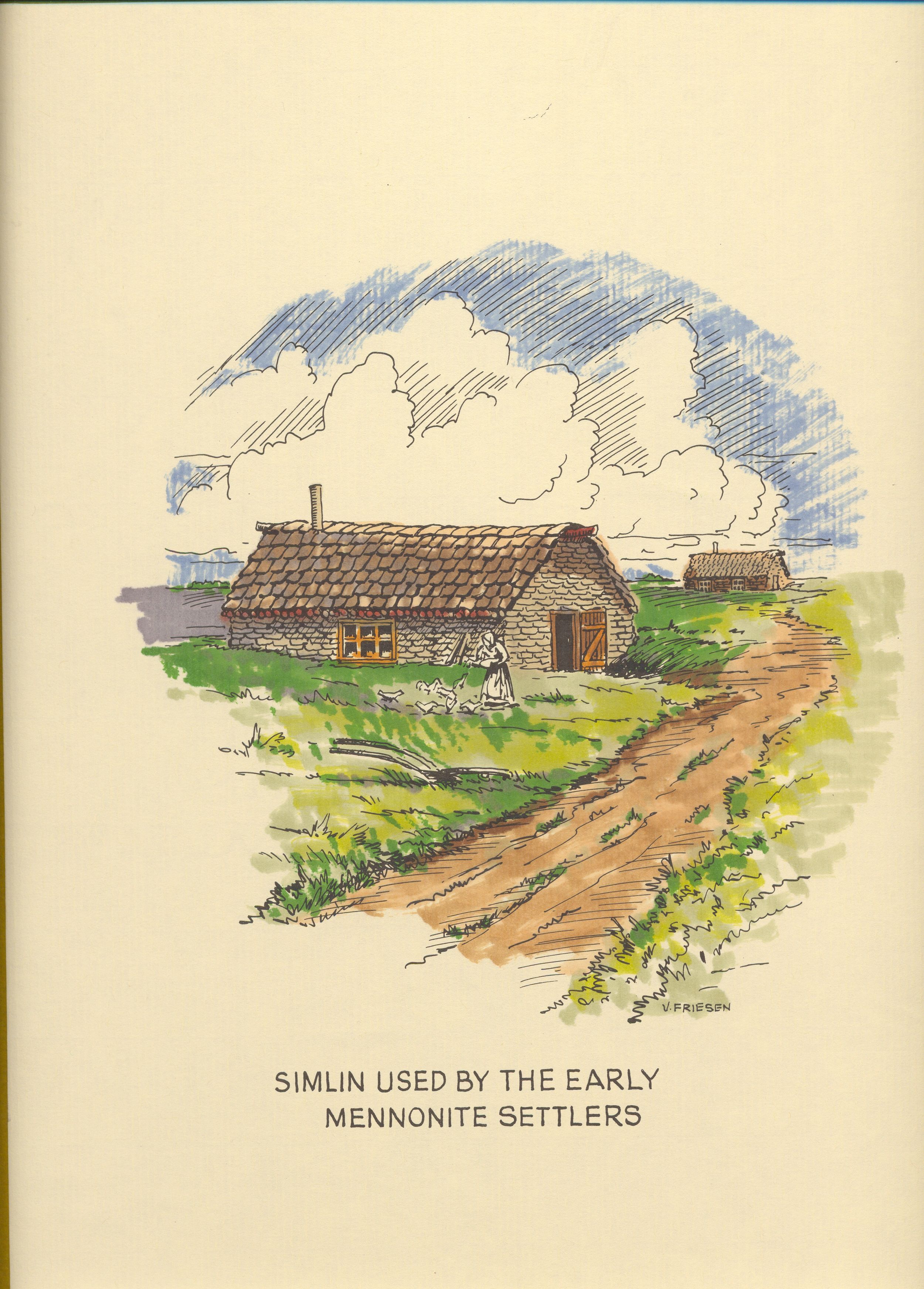

Semlin by Marta Goertzen of Chortitz - provided by Mennonite Heritage Archives

Semlin by Marta Goertzen of Chortitz - provided by Mennonite Heritage Archives“This John Dennis, he was impressed that the Mennonites paid back their loan in 1892, and he was now a commissioner. He talked with his boss... and said, ‘These Mennonites are good for it.’”

Mennonites and community

Why are there villages celebrating 150-year anniversaries this year? For Stoesz, it was something that needed to happen to make the area liveable.

“Community was an essential part of their success. They leaned on each other. They had to. In the West Reserve — on the open prairie — there were no other settlements there. Other Europeans didn’t want to create communities there because it was such a harsh environment.”

No trees to build a house, to build a fence, or to burn for heat, any Manitoban who has spent a winter in the tundra desert can attest to the fact that one would not want to get caught in the cold alone.

“To do that all on your own is really difficult. But if you can do that as a community, then that works,” he said, pointing to things like food production, childcare, health, agriculture, and smithing as all things that could only be done thanks to the community those Mennonites surrounded themselves with.

Semlin by Victor Friesen 1974 - provided by Mennonite Heritage Archives

Semlin by Victor Friesen 1974 - provided by Mennonite Heritage Archives“So based on their reputation that was established in 1874, was established in 1892... almost two million dollars was lent to the Mennonites coming in the 1920’s all on a handshake.”

Related stories:

- Two friends are turning lemons into lemon-aid for CancerCare Manitoba

- Morris rolls out the rodeo: Manitoba Stampede brings big fun to the Prairies

‘If we're not going to tell our story, who is?’

Stoesz has dedicated his professional life to documenting history. To remembering the stories that make us.

“We all live by stories. Stories are central to who we are, and if we’re not going to tell our own story, who is?”

Our own stories have a way of landing in a powerful and unique way when open to them, and it’s the things like anniversaries that tend to pull that out of people.

“The anniversary provides an opportunity to look at the past. We don’t have to accept everything that they accepted. We don’t have to have the same values our ancestors had, but by looking at the anniversary... people tend to come together. There’s a gathering that comes with anniversaries.”

And as these communities gather to remember their stories, it’s worth noting — the people they remember were once remembering, too.

- with files from the Mennonite Heritage Archives -